The Paris-based designer Raphael Navot is first and foremost a storyteller. For each project, he executes everything from the concept and design of the space to the custom furniture and fittings. Each space he designs is unique and defined by the essence of the purity of form, the use of noble, raw natural materials and his high regard for craftsmanship. With his unique design language and artistic sensibility, he chooses his projects with much thought and care and although he works in architecture, interior design and furniture design, he considers himself a “non-industrial designer”.

Born and raised in Jerusalem, he attended the prestigious Design Academy Eindhoven in The Netherlands. During his studies, he caught the eye of Lidewij Edelkoort, the renowned trend forecaster and, at the time, university chair. After his graduation in 2003, he went to Paris to intern for Edelkoort where he worked for the forecasting magazine View on Color. Six months later he launched his career as an independent designer. His diverse portfolio of work includes projects such as the interior design and creative direction of the highly lauded and internationally recognized Parisian nightclub Silencio (in collaboration with the film director David Lynch), the Hôtel National des Arts et Métiers in Paris and the newly redesigned Parisian restaurant, Le 39V, along with sculptural furniture and design objects, which are now being represented by Friedman Benda Gallery in NYC. He has long called Paris home as its historic tradition with savoir-faire is something that feeds his creativity. We recently spoke with Raphael to find out more about his singular style, his unique working process, why craftsmanship is important to him and why writing is an important part of his creative process.

You did Conceptual Design as your degree?

Yes, I studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven, which is known to be a school that is focused on design thinking, so I’m not coming from a background that is technical. I think it’s more the philosophy of design. It was more abstract as we were studying the concept of “why we are creating”. Back then it was really a school that put the person at the center allowing the students to discover where they design from rather than what do they wish to design and that’s why there were departments that were called “Men and Well-being”, “Men and Leisure”, “Men and Activity”, and instead of calling it “Fashion Design” it was “Men and Identity”. We were doing more group studies while we were creating and working on eccentric projects that challenged our intellect.

Did you think that you were going to do interiors?

No, not at all! But you know now, funnily enough, working on interiors seems to have been a stepping-stone for me, and now I feel more connected to design and craft than ever before.

Is that from working with artisans on your projects?

After graduating from the Design Academy, I followed Lidewij Edelkoort to Paris and I was working in different fields within arts and crafts. I was actually making my own pieces by hand, something between sculptural and furniture pieces. For me the distinction between design and art, I think it’s quite new, and I remember that in Holland they called design “form giving”. If you go and study crafts or anything about decorative art, art and functional design will never form a unit. Art and functionality have not always been as separate as they are today. The principle of “form follows function” can be seen in reverse – “function follows form”. Any of these versions is what I call design. I am working in different fields now, from large scale editions to hospitality to gallery pieces and to be honest the question in the end is always about the limitation, I mean where are the constraints that lead to a design? What are the conditions? What is the context? So, I think that it is just the surrounding for me that is changing but not the way I work, it is only the territory that is different. I apply the same principles to each project. I don’t see a difference in making jewelry or designing a building. It’s about semantics, materiality and expression.

When working on a project, are you creating everything or do you bring in, for example, vintage pieces or work by other people?

Essentially, yes, I create everything. I prefer this especially for hospitality where I feel like one enters a universe, similar to Silencio, the Parisian underground club that I designed, and there are areas in which you live that are isolated from the world. It’s a bit of the opposite when you go really underground, and it never ends. You kind of live in a bubble of a micro universe and, for example, with my recent project at the restaurant Le 39V, you go up to the rooftop and have this inverted panorama into the center of the space where a floating 100 year-old olive tree is located. Instead of having a panorama on Paris rooftops, the space is inverted upon itself like a floating ring. This is why I thought that a tree can be the most adequate centerpiece. A celebration of nature. In the past, architecture was so particular. I like the idea of old school architecture when you enter a space and everything is bespoke and made according to the parameters of the space. I do use some design pieces, especially chairs, I tend to buy chairs and not to design them because it takes a lot of time to develop. But what I do for each space is to introduce a group of craftsmen and with them we develop new materials. We even make new textiles; colors were made for projects. I feel like it’s something romantic. That’s why I’m not really a decorator, or an interior designer, I’m more of a designer: I draw, I develop concepts and I happen to do interiors.

Back to the restaurant, Le 39V, some sections felt like a cocoon, was that all wood or fabric?

The whole space was actually very angular, so I wanted to soften it. I fell in love with the idea of a space being somewhat futuristic and very natural, and having an optimistic future with technology. I like to think of it as a “natural future”. So we have everything hidden but the space still has a very minimal presence. We have Taj Mahal marble, wood and silk and mohair. All kinds of tactile materials, some are more noble than others. For the seating area by the bar, I used a foam with a special textile to make it more acoustic. There is a “fresco wall” where we created a gradient from browns and blues to warm white that is similar in feeling to the ocean. The tables have rounded corners and echo each other. I wanted to create a feeling of a futuristic science fiction set – to create a “nostalgic future”.

In your work you are known for your love of materiality.

My inspirations are derived from the materials themselves. I hardly work with aluminum or polymer. I work with earthy materials such as stone, wood, iron. These are corporal materials, you understand them. You can lay your hand on a massive stone or wooden table and you can feel its history, how it is linked to nature. For Oscar Ono, I created an end grain floor that took five years to develop. I like to push the craft. I am using a very old technique of parquetry, but in a contemporary way with a spiral movement. In my designs I am not being referential, I am not looking at design movements but instead I am inspired by geology, biology, by just listening and tapping into the knowledge of the artisans that I work with and I am greatly influenced by them. Good design should ask “what” – what is possible with wood, what can I do to push its capability.

For the travertine console and bronze table and lamps in my “Topographic Memories” series, I made the drawings and then we modeled everything using 3D technology. I worked with the artisans at Ateliers Saint-Jacques and for the table and lamps we did a bronze casting of each piece like in the Middle Ages. I use technology as a planning tool but not in the execution. I did the texturing by hand. The travertine bases were burned and immersed in water. This quick shock mimics the hundreds of years of time that it normally takes to create this coral like look. I am mimicking time by the process we use to create the effect.

For the “Senza Misura” table for Friedman Benda Gallery, it was inspired by the form of the palm of one’s hand. To create the patchwork assembly, I used the 7,000-year-old tradition of “mortise and tenon” (putting together two pieces of wood without the use of nails or glue). It is a “know-how” that is sadly going away as there is only one craftsman in France who can do this. To create the design, one is working with the forces of the wood and it is creating a tension. When I am creating something completely new, I have a lot of discussions about the design with the artisans and they come up with solutions. My ideas push the limits of the materials and they are responsible for the end result.

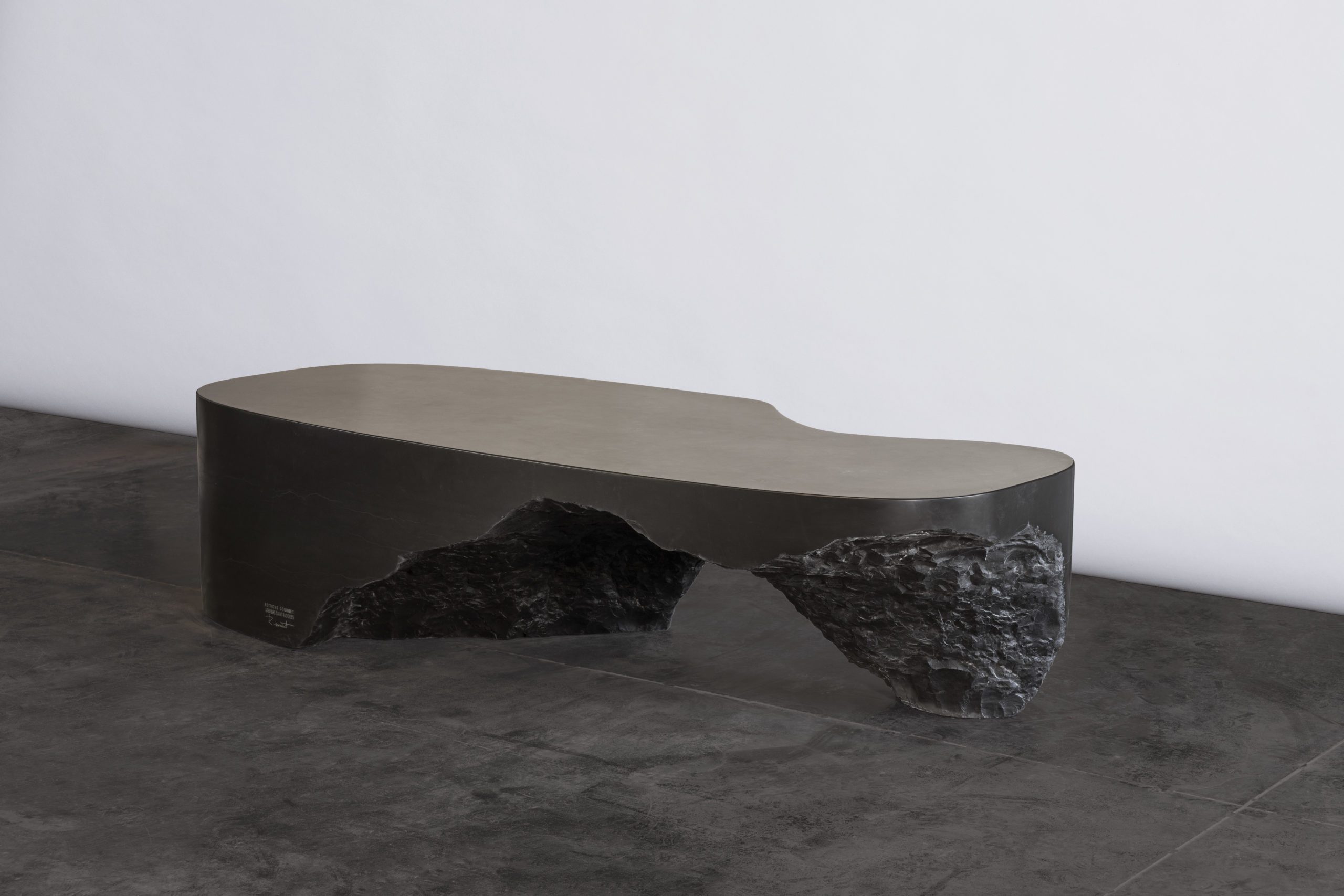

I am fascinated by your “Eyes” bench. It looks like it was something unearthed from the ground and it is telling a story through a new language, like hieroglyphics.

For the “Eyes” bench, the wood pieces that I used were rejected pieces from the wood industry. We tend to prefer our wood straight and calm with as few “surprises” as possible. The industry is constantly inventing methods to control it. I find these errors very meaningful and to be telling an important story – a knot can represent the birth of a branch, or a scar tells the story of a terrible storm. It is a language of celebrating the faults of the wood. Each “eye” is unique. I found an amazing artisan in Belgium who could create this piece. To attach the small pieces of wood together, we used rubber that is typically used on boats, as it is a natural material and allows the wood to move during the extremes of heat and cold. The black burned wood frame was a result of using this black rubber on the top. The design solution came about from the materials we used. The materials tell a story – there is something to say.

Your made to measure environments are so carefully thought out and executed. How long does it take to complete a project?

It takes time to create these projects. Le 39V took 1 ½ years. My newest project that just opened, Hôtel Belle Plage, took 3 ½ years to create. It is a newly built hotel and spa in the quiet center of Cannes (by the same owners of the Hôtel National des Arts et Métiers). I designed the whole building inside and out and used local craftsmen. The advice that comes from seeing centuries of heritage and craftsmanship is “take your time”.

What advice did you receive that resonated with you?

It was from Li Edelkoort who told me that a career happens when you are ready. I have been working for 20 years, but the last 5-7 years I really feel like I am doing what I am supposed to be doing.

Are there any other designers that you admire?

I think that there are many interesting minds out there that celebrate the idea of timelessness instead of rushing to the new or working too hard to stay in trends. I like the works of Festen, Faye Toogood, Ilse Crawford and artists such as Byung Hoon Choi.

Do you collect anything?

I collect materials about the natural world such as algae, and drawings about natural history, biology, geology, and types of stones.

I was so surprised to hear that you don’t have an office.

I work independently. So many creative people are independent. For each project I set up an office that is usually on site. I think of it as a “nomad office”. I work with local architects, artisans, and ateliers. I put together a team that is best suited for a specific type of project. I enjoy working on projects together with the artisans etc., but it is tough for me to create in a team, so in the conception phase I work on my own. I like having the office on site at the project as all of the artisans, engineers and architects can join us in the space to discuss ideas instead of working together virtually or imagining the site. Working this way, we are all there together. There is a disadvantage to this working style as I can only take on a few projects at a time and growth in a linear way is not possible, but it is a relief for me. I try to take the right projects and create a story with the owner. I wouldn’t take a project that was oversized as the small team has to handle it. The advantages of this way of working allows me a certain liberty. Many designers find themselves successful but with a big office and a “machine to feed” and projects they are accepting in order to support their staff. That scares me. I don’t want to lose the ability to discuss with my clients directly and to understand their needs. I want to see the craftsmen and to visit their workshops and talk with them. I am a designer, not a businessman and I am not a commercial entity.

You are known for your attention to materials, but also your attention to craft.

There is something about craft, the touch of the hand, the work behind it, the magic of just the material itself and the fact that we can actually see and feel the tradition, the heritage, the knowledge that is so embedded in the piece itself.

I find it easy to recognize a crafted piece, which for me means that it is just a piece that was given more attention. Somebody gave it more attention, somebody invested in it. Lots of “know how” is being lost. This important heritage, this savoir faire is something that we need to protect and we need to get to the future without losing this “know how” – we need to find new ways to bring it with us into the future.

France is a haven for craftsmanship, of renowned expertise. I work with Jouffre for my upholstery projects as they respect the tradition. They have a high level of luxury craftsmanship. I like to challenge the craftsmen and use different materials such as cashmere, silk and oak that we used for the “Acrostic” pieces that I created with them. With them I feel like any idea I have is possible.

I find it interesting that you don’t do residential projects.

I work mainly in hospitality projects and furniture editions. I want to work on projects where the owner wants to tell a story. There is a sensory feeling. With these clients, I can get to the story that they feel comfortable about for the space. But with a private residence it is their home. It is tough for me to say, “this is how I think you should live”. It is difficult as I don’t want to impose my style on them. The client will not know what the end result will be, as for example I don’t pick out paint colors together. My style is not coherent with pre-determined selections of furniture and colors because I don’t know the outcome until the project is completed as it is an organic process. I don’t fit that category of a typical interior designer. I don’t have a style that keeps repeating. I am trying to create an aesthetic that is somewhat timeless. It could have been from 50 years back or from 50 years in the future.

In designing hospitality/commercial spaces, the real client for me is the guest of the space (not the owner) and the next client is the staff who works in the space. If my design serves the guest and the staff, then the client should be pleased.

Do you follow what is going on in the design world and what is current in terms of trends?

I don’t deliberately follow trends but sometimes it follows you. I am not a big fan of the word “trend” in general. I think especially when you talk about what has always been good and will be good there is not much change in that. However, I do find it very exciting when people ask for something we haven’t seen before but feels like it has always been there. In the end, the search for beauty of form is more important than the need to follow the trend of the moment.

What inspires you when you start a new project?

I start every project by drawing and writing. Writing helps me understand the intention, the core of the project, the values, what is the space about, the atmosphere. For me, writing is very important in the creative process. The design is the last part. When I began thinking about the design for the Hôtel National des Arts et Métiers in Paris, I walked around the neighborhood and thought, “what is craft in Paris – copper, chalk, stone, granite”. I wanted the craft seen around the city to echo inside the hotel. The colors we used came from a color that abounds around Paris – oxidation. It is Paris’s signature color. So, blues and rust were our main color chart. Most of the colors I use in projects derive from the materials themselves. I hardly used any paint in this hotel.

I create a story for each project. I create mood boards, I think about the artists of the time, of history. I have the script and I just need the casting (of the artisans).

Raphael Navot will have a solo show at Friedman Benda in NYC this October.

To discover Raphael’s projects please click here